Teletimes – Success of Pak telecom sector is recognised globally

Minister Incharge/ Advisor to Prime Minister for Information Technology, Muhammad Latif Khan Khaosa has said it is a a known fact that the success of Telecome sector in Pakistan is globally recognized.

Read MoreDaily Jang Rawalpindi – Industrialization is needed to bring Pakistan out of the economical crises.

There is a high competition in the international markets, the success is behind the use of low voltage and automation.

Read MoreManagement of Information System

Carnegie Mellon Management of Information System Certificate 1989

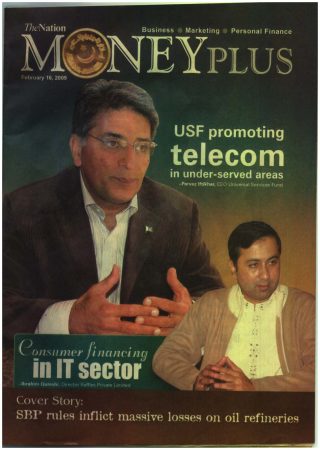

Read MoreUS Promoting Telecom in under-served areas

February 16,2009 The Nation – Money Plus: CEO Universal Services Fund, Parvez Iftikhar talks to Saadia Qamar to highlight the role of this company in promoting telecom services in the remote areas. Please Click Here to continue reading.

Read MoreTeletimes – Universal Services Fund Awards

USF, Ministry of IT, awarded two contracts worth Rs. 1.037 Billion in total for providing Broadband Internet Services in the un-served urban areas of Central Telecom Region to PTCL and Wateen Telecom.

Read MoreDaily Khabrain – Siemens company will continue its operations in Pakistan with the co-ordination

Pakistan can get out of its economic crises by making fast progress in the sciences & technology.

Read MoreCertificate of Human Relations Seminar

Pakistan Institute of Management Certificate of Human Relations Seminar 1990

Read MorePakistan Observer – Parvez Iftikhar’s Profile

Mr. Parvez Iftikhar, CEO of USF Co. Pakistan, is a telecom engineer with over 30 years of experience.

Read MoreDawn Islamabad – Universal Service Fund: CEO’s note

April 22,2010 It is with great satisfaction that I look at the thriving entity that Universal Service Fund Co. is today, espacially when I compare it with the day I joined three years ago as it’s first employee, when my first tasks were hiring of a professional staff and refurbishing/ furnishing of office in the…

Read MoreDaily Qaumi Akhbar Karachi – Telented Students should be encouraged

This valuable resource should be used for the country. Address by Dr. Abdul Hafeez Sheikh at Siemens gold medal award ceremony.

Read More