Blog

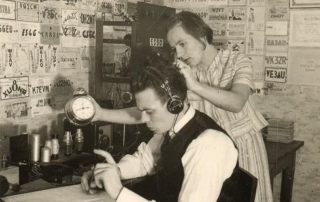

Childhood and Universal Service

Back in the early sixties when I was a school-kid – long before our Bengali brethren were alienated by military-rulers and feudal politicians, and when the relations between the then East and West Pakistanis were sweet and friendly - my father, a young Signals officer in the army, posted in Dhaka for a couple of…

Read MoreITCN Asia 2014 – 3/4 G Impetus to growth

“This question may only be answered by someone who does NOT agree that YouTube should be opened”, I jokingly challenged the panel of eight high-profile experts sitting on the stage when a young participant at ITCN Asia 2014 (Karachi, 26thAug ’14) stood up and, lamenting the losses to the youth due to YouTube blockage, asked…

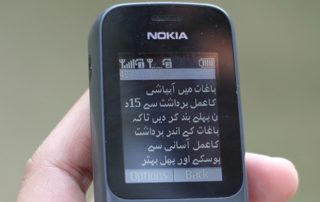

Read More3G and 4G – what a waste…

If you can read Urdu, read the text on the accompanying picture and imagine (in case you can’t read the text, even then imagine!) how would it be if same information is conveyed to the agriculturists using VIDEOS! And imagine if these videos could be seen on cellphone screens of the targeted growers of the…

Read MoreMy first time in Liberia

As I write this, I am returning from Monrovia, in Liberia, a country that has a rather interesting history. It was the first republic in Africa, established back in 1847 for the liberated slaves of America (hence the name 'Liberia') who were brought and settled here to work on rubber and palm plantations (some kind…

Read MoreMy first time in Rwanda and ICT4Ag Conference

I was in Rwanda (3 – 9 Nov. 2013) on the invitation of CTA (French acronyms for “Technical Center for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation” – www.cta.org) to the 4-day ICT4Ag (ICT for Agriculture) conference to speak on the importance of Universal Service Funds in providing connectivity to rural areas. My presentation (together with two others)…

Read MoreWhy does Pakistan need 3G

My blog in the daily "Express Tribune" of 7th September 2013: http://blogs.tribune.com.pk/story/18750/why-does-pakistan-need-3g/

Read MoreDid the new IT Minister really threaten to ban Google in Pakistan? My Blog in daily Tribune, 14-Jun-2103

Below is the link to my blog as it appeared in the daily Express Tribune on 11th June, 2013, titled: "Did the new IT Minister really threaten to ban Google in Pakistan?" https://tribune.com.pk/article/17688/did-the-new-it-minister-really-threaten-to-ban-google-in-pakistan

Read MoreWhat Anusha Rehman should do for Information and Communication Technology – My Blog in daily Tribune, 11-Jun 2013

Below is the link to my blog, published in daily Express Tribune on 11th June 2013, titled: "What Anusha Rehman should do for Information and Communication Technology" http://blogs.tribune.com.pk/story/17638/what-anusha-rehman-should-do-for-information-and-communication-technology/

Read MoreI have a problem with GSMA!

I have a big problem with the findings of the recent otherwise very comprehensive and detailed GSM Association sponsored report on Universal Service Funds (GSMA Resources). It has been prepared by Ladcomm Corporation, compiled mainly by the well known fellow consultant Lynne Darwood. No praise would be too high for the amazing amount of information…

Read MoreMy participation in USF Workshop of APEC TEL 47

Such is the importance being given to Universal Service and Broadband all over the world that if you look at the APEC TEL Strategic Action Plan: 2010-2015*, the very first item is: “Universal access by 2015 – Expand networks to achieve universal access to broadband in all APEC economies by 2015”! So when I got…

Read More